In Rome, in the year 1606, the monks of the church of Santa Maria della Scala stood waiting with bated breath to see the painting “Death of the Virgin,” finally completed by the most important artist of his era, the artist known as Caravaggio. He had spent four years working on this painting. The excitement was very high, and everyone was anticipating a great work from a great artist depicting great figures. The truth is, my friend, amidst this state of preparation, people looked and were shocked by the painting!

After looking at the painting, the monks said with disapproval: “This is not the Virgin! Who is this ugly woman?! Where is the light?! Where are the angels?! Where is the sanctity of the painting?! Is this the best artist in Europe?!” The truth is, in his book Caravaggio: The Complete Works, the author states that the church’s shock was due to Caravaggio’s departure from the traditional way the Virgin was depicted, which usually showed her as a luminous, sacred being.

What Caravaggio did in this painting, which was strange to them, was that he replaced her with the body of an ordinary human woman, showing signs of death. If you look at the picture, you’ll feel like you’re in a theatrical scene: a large red curtain descending from the ceiling, like a stage curtain; strong lighting on the Virgin’s body and the faces of those present, while the rest of the scene is drowned in darkness. The problem is, this isn’t a play.

This isn’t a performance. It’s a very realistic scene, a sad human death. The heroine here is a very ordinary woman. The Virgin in the middle of the painting is lying on a modest bed, her stomach slightly bloated, her face lifeless. There is no holy halo around her face. Her leg is bare and hanging down, as if she suddenly fell from life. If you look around her, you’ll find figures like the apostles and Mary Magdalene, all looking down, grieving.

The strange thing here, as I told you, is that there is no depiction of an epic moment, divine light, or sanctity. There is no sanctity in a painting of sacred figures! The painting contains realistic bodies and realistic sorrow, as if we are at an ordinary funeral. The truth is, let me surprise you and tell you that the monks’ shock wouldn’t stop there. Because when the monks looked for the model Caravaggio chose to represent the Virgin in this painting, they discovered it was a real corpse of one of the prostitutes he knew! “Good heavens!” One day, this girl drowned in a river, so they brought him her body to paint her as she was, dead.

It feels like we are in front of a strange artist who paints a sacred painting but shies away from depicting holiness. Instead, he creates a realistic depiction of pain and sorrow. Perhaps, to understand this painting, we need to understand this artist’s childhood.

From Milan to Rome: A Childhood Forged in Plague and Pain

On September 29, 1571, our hero was born in Milan on the feast day of the Archangel Michael, which is why his family was optimistic and named him Michelangelo. His father was a decorative architect working in the town of Caravaggio, and later, as you might expect, he would take his name from it, just as we might call someone “al-Dimyati” (from Damietta) or like “da Vinci,” which meant “from Vinci.” Caravaggio would become famous by the name of his town to differentiate him from the legendary artist Michelangelo, who had died just a few years earlier.

The most important person in Caravaggio’s life was his mother, who was a source of protection and comfort, especially after his father died of the plague when he was just a six-year-old child. The boy stayed with his mother for a while, and then she too died when he was 13. Thus, Caravaggio lost his entire family. If we go back to the painting, we find that according to some analysts of Caravaggio’s art, the expression of grief in this painting is not religious but human, personal, subjective.

The body of the Virgin, as I explained, is human, not ideal, not luminous; it’s the body of an ordinary, tired woman, like a housewife who struggled and toiled in the world, just like his mother. Even Mary Magdalene, who was sitting and crying, some researchers believe she represents Caravaggio himself, or more precisely, the child within him, still standing before his dying mother’s body, unable to speak, but able to cry.

The greatness and artistic genius of the painting, and its presence in major museums today, would not save it. The monks rejected it, and it was removed from the church. Today, this painting is in the Louvre Museum. The death of his parents certainly shrouded Caravaggio’s childhood in sorrow and made it difficult and harsh. This meant he had to work and rely on himself. In the same year his mother died, he signed a four-year apprenticeship contract with the artist Simone Peterzano. This was a crucial formative period because it allowed him to see the art icons of Milan, such as da Vinci’s “The Last Supper” and the Lombard art, which valued simplicity and attention to natural details.

“That’s beautiful, Abu Hameed! It’s good that the boy didn’t give up and kept working.” Unfortunately, my friend, perhaps because of what happened in his life, Caravaggio was described as arrogant, rebellious, and quick-tempered. His mood swings were very sharp. He loved drinking, gambling, and was always ready to get into a fight, which made him difficult to deal with. He finished his apprenticeship, and in 1591, he left Milan for Rome. Why? Because there were many complaints against him. “What did he do, Abu Hameed?” He wounded a police officer.

A New Technique for a New Realism: Chiaroscuro and The Fortune Teller

Caravaggio arrived in Rome very poor and in a difficult situation. He remained in this state until he started working with a man named Giuseppe Cesari, who was the favorite painter of Pope Clement VIII. Cesari specialized in painting flowers and fruits. At this time, Cesari began to use a painting technique called Chiaroscuro, a term that refers to the contrast between light and dark. This technique describes the interplay between darkness and light in a way that allows the artist to work effectively on the mood of the painting and the character he is working on.

If you don’t understand, my friend, let’s look at Caravaggio’s painting… “Boy with a Basket of Fruit.” If you look at this painting, you’ll feel that Caravaggio’s talent began to mature, and he started to become somewhat known. We also see another famous painting of his, “The Fortune Teller.” This seems like a scene from daily life in Rome.

An elegant young man, believed to be a friend of Caravaggio, is standing with a gypsy girl reading his palm. I want you to focus a little, my friend. You’ll find that what appears to be an innocent fortune-telling is actually a scam. While the girl is holding the young man’s hand and predicting his future, her other hand is deftly stealing his ring!

This, my friend, is one of the key features of Caravaggio’s art. He chose a seemingly traditional subject, like an ordinary daily scene, but expressed it with his brush from a new perspective, and perhaps, if he wished, he would add a twist in the middle, some action happening. Not just a beautiful painting, a nice frame, beautiful compositions, and lovely elements. “No, I will add action. I will add theft, a scheme, things you’ll notice if you pay attention.”

At that time, most artists of his era painted noble subjects—religious, moral, or mythological themes. Society was conservative, and the Church was the most important client for artists. “So we have to make things the Church will be happy with to get its support.”

Caravaggio comes into this society and decides to depict the less noble scenes of European life. “The daily life where you artists choose the beautiful, the noble, the sweet, the moral, and the sacred, I will choose the ugly. I will choose the morally low.

I will depict the reality of society. I am a damn man, brother!” In this painting, we’ll see Caravaggio’s distinctive use of shadow and light, which, as I told you, is Chiaroscuro. A strong light is cast on the main characters. The young man is unaware of what is happening, and the girl looks on with a cunning expression, as if making us, the viewers, partners in her deception. This was a new style for the society at the time and would make this work successful.

A Powerful Patron and a Volatile Genius

Although the painting was published, its most important success was introducing him to a man named Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. This man was a patron of the arts, a very important sponsor in the art world at the time. A man who loved beauty and thought, and unlike the majority, he was open to new and different things, especially if they had courage and humanity. “We want to do things from the street, we want the pulse of the people!” And of course, Caravaggio excelled at this.

You want realism? Here you go! The truth is, those around Del Monte were surprised. How could he sponsor a troublesome, violent, and fugitive young man? But Del Monte greatly appreciated his art. He saw that this boy was an extraordinary talent, a raw, untamed talent. He took Caravaggio under his wing and housed him in his palace, the Palazzo Madama.

This sponsorship would change Caravaggio’s life forever. He moved from a life on the streets to the refined cultural elite. The Cardinal introduced him to the upper class of Rome: nobles, clergymen, and artists. This was what Caravaggio needed: patronage and trust. Here, Caravaggio’s talent would explode, and he would become the most important rising artist in Rome, commissioned to paint for churches and palaces. And here we begin to see a strange phenomenon: palaces and churches receiving paintings from an artist who sometimes strips his art of the sacred and the beautiful, revealing its truth with a very captivating and shocking art.

At the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century, recurring problems began to arise between Caravaggio and the Church. Caravaggio depicted the saints as ordinary people, with simple clothes and tired faces. By the way, this realism of Caravaggio would remain attractive for decades, if not centuries. We see someone like Pablo Picasso, when painting his “Guernica” mural, saying he wanted to paint a horse so realistic you could smell it, like Caravaggio’s horse in the painting “Conversion of Saint Paul.”

He began to develop the Chiaroscuro technique and invented another style from it called Tenebrism, an Italian word meaning “dark” or “gloomy.” In some paintings with this technique, you’ll notice that the background is black, in one way or another, and the main characters in the painting are illuminated as if they are emerging from the heart of darkness. The light itself is very focused, like a beam from a flashlight or a small window in a dark room. What would cause a problem with the Church was that Caravaggio would bring the saints, the heroes of his paintings, without the ideal luminous halo we were used to in previous art.

Judith Beheading Holofernes: Redefining Religious Art

Let’s look at paintings by great artists depicting the Book of Judith. We have the story of a Jewish woman named Judith who killed the Assyrian general Holofernes to save her people from invasion. If we look at a painting by a great artist like Botticelli, Judith appears as an elegant goddess, holding a sword, her face full of peace and contentment. Her enemy’s head is not clear. The idea here is more symbolic than bloody. Beauty is victorious without blood.

When we come to the “Mohamed Khan” of art, our Caravaggio, we find he chose the most dramatic moment: the moment of beheading itself, not before, not after. If you look at Judith here, you won’t find a sense of victory or happiness. On the contrary, you feel that as she kills her enemy, there is an internal moral and psychological conflict within her. There are two conflicting feelings inside her: the determination to do this act and the rejection of the idea of killing. Her face says: “I don’t want to kill, but I am forced to do this!”

Caravaggio understands the algorithm. The rule of screenwriting says, “Arrive Late, Leave Early.” This is what Caravaggio does. He brought you a picture, a painting, no movement, no action, no soundtrack. “I will choose a scene, a picture, that contains all the action, the peak of the action.” And unlike most painters who keep the scene clean, Caravaggio will make the scene bloody, with tense muscles and a neck being slit, which is Tarantino before Tarantino! A moment of death is happening, and you, the viewer, are a witness.

Of course, my friend, the painting would be released, and the clergymen would say: “What are you doing?!” They saw a kind of impudence and excessive violence in it. They also felt it was disrespectful to the sacred stories. But despite these reservations, people, especially the youth, were fascinated. They saw in it a new vision of art, far from the idealism that previous artists practiced. They saw the raw truth, they saw pain, they saw weakness, they saw evil. And this was rare for them.

The violence in Caravaggio’s paintings was not a product of his imagination but was influenced by the violence he saw in his daily life. It’s true that at that time, Caravaggio was the most important artist in Rome, and his fame was overwhelming, but this fame was not only from his art, but also from his violence and crimes. Once, he was sitting in his patron Del Monte’s palace and got into a fight with an aristocrat, drew his sword on him, and cut his cloak, so he was imprisoned. Another time, he and his friends beat up a passerby.

He was also arrested for carrying a sword or dagger without a license, and once he threw stones at an officer, and once he had to flee Rome for weeks. Why? What did he do? He beat a court official. Caravaggio was a thug!

The Calling of Saint Matthew: A Masterpiece of Light and Doubt

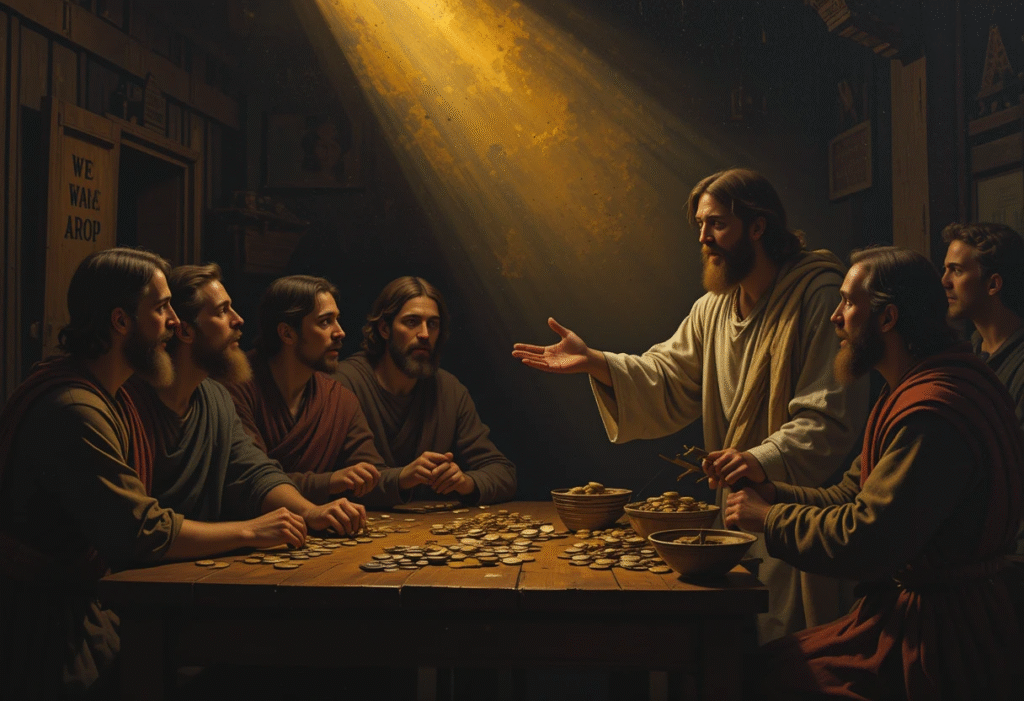

But look, for example, at his painting… “The Calling of Saint Matthew.” You will see, my friend, a magnificent work that reaches perfection. “As Jesus passed on from there, he saw a man named Matthew sitting at the tax collector’s booth. And he said to him, ‘Follow me.’ So he arose and followed him.” In the Gospel, we read an instantaneous reaction, something fleeting. But Caravaggio: “Wait, wait, wait! One second, one second, one second! Stop! No, wait! Where’s the drama? Bring out the drama from here.”

In this painting, he created a moment of doubt. We find Christ pointing to him and saying, “Follow me.” But then we find a moment of doubt from the saint, as he points to himself and says, “Who? Me?!” If we look, my friend, through the lens of a film director, the scene is shot in a closed room, a window, a beam of light piercing the space, creating a contrast between light and shadow—his game. This gives a strong sense of the moment’s drama and excitement. The light is not natural; it’s more like a revelation, a symbol of Christ’s presence and the light he brought to the world.

You will notice the similarity between Christ’s outstretched hand in the painting and God’s hand in “The Creation of Adam” by whom? By Michelangelo. The similarity points to the idea of creation and spiritual rebirth. The hand grants another life, a new life to the saint and to every believer. Look again, my friend, at the saint. You won’t find him happy.

He is in a state of astonishment, a state of shock. This is a very rare moment in religious art, because most artists, when they depict saints, show them with clear acceptance, submission, and surrender. But Caravaggio here is telling us, in one way or another, that true faith comes in the heart of doubt, amidst the hustle and bustle of life.

From Fame to Fugitive: Murder and Exile

Let’s go back to 1606, the year we started our episode. We find Caravaggio as the most famous artist in Rome, dividing people around him into two teams: a team of admirers, followers, and students who adored him, called the Caravaggisti, like the BTS Army. On the other hand, we have a team of critics who saw him as corrupting public taste with criminal, ugly, and vulgar art. But as you know, any publicity is good publicity. These criticisms only increased his fame and appeal to the public. Perhaps the most fitting title for Caravaggio is considering him the founder of Baroque painting.

Between 1545 and 1563, the Council of Trent was held 25 times. This was one of the most important church councils in the history of the Catholic Church, held in reaction to the Protestant Reformation led by Martin Luther. The Church was aware of the importance of art and saw it as a crucial means of strengthening people’s faith. Art’s purpose was not just to display beauty and decoration; no, it had to be influential, affecting people to make them understand their faith and have feelings for their saints. Art that makes them feel faith, sin, and salvation.

The Baroque style was different. It was like a dramatic cinematic scene at its climax. “Forget the light of the Renaissance. I’m not going to sit and watch someone like this, not knowing if they’re looking at me or not, and call it art! There is movement, emotion, and drama.” The colors are strong, and the contrast between light and dark is sharp. The characters seem to be moving, writhing in pain, or screaming in fear, or exploding with emotion. The goal here is not beauty; the goal is for the artwork to shake you from within, to make you feel that you are with them in the moment.

Caravaggio, who was born about 10 years after this, was the perfect embodiment of the Church’s slogans: art that moves emotions, not just decoration. And indeed, over time, he became the founder of this Baroque art. But while the Baroque was fueled by political and religious transformations, Caravaggio’s art would continue to be fueled by one thing only: violence. Violence that would begin to explode with him more and more! In May 1606, Caravaggio doesn’t just insult someone, or wound someone, or threaten someone with a sword. No, he kills someone: Ranuccio Tomassoni.

Some said it was a fight during a game of pallacorda, a game similar to tennis, and things escalated until Caravaggio stabbed him. The Pope sentenced him to death. And here, Caravaggio flees the country.

He begins to flee to Naples, which was under the rule of the Spanish crown. Naples would welcome this fugitive killer as an artistic legend. There, he painted some of his greatest works, such as “The Seven Works of Mercy” and “The Flagellation of Christ,” paintings in which you feel a clear transformation in his spirit and his art. The escape and exile were reflected in every brushstroke, becoming darker and full of violence, regret, and pain!

A Knight’s Fall and an Artist’s Confession

After about a year in Naples, in the summer of 1607, Caravaggio travels to Malta, which was under the rule of the Knights of Saint John. This was a powerful military and religious order. Caravaggio went there seeking asylum and hoping to receive the title of “Knight” from them. If he had received this title, it could have helped him get a pardon for the terrible crime he committed in his country, and then he could return to Rome.

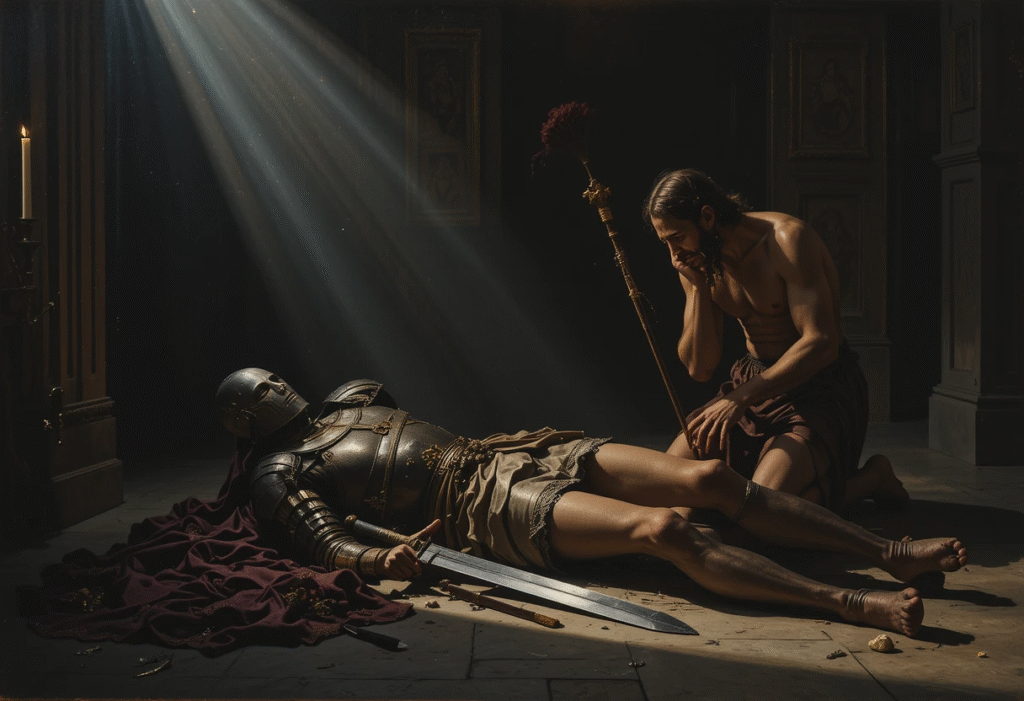

Indeed, the Knights were very impressed with Caravaggio, and he painted a work for them that glorified them, so they gave him the title of “Knight.” But then Caravaggio gets into a fight with a knight of higher rank, is arrested, and imprisoned in the castle’s fortress, one of the most fortified prisons. But of course, Caravaggio, like his mysterious and strange life, manages to escape. But before he escapes, he leaves us a magnificent work, as usual. Caravaggio presents us with his largest painting in size: “The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist.”

As you might expect, most artists paint this scene at the end, after the action has already happened. Caravaggio, as usual, chooses a clever and dramatic moment: the moment of the beheading itself.

We see John lying on the ground, still breathing, his blood flowing. The executioner is holding a small knife to finish the job after already wounding him with the long sword. A prison guard stands watching, Salome holds a golden platter, waiting for the head, and her maid is shocked by what is happening! But notice the strange thing here: she is covering her ears, not her eyes. Covering the ears is a human reaction to violence and pain that we are unable to face, but also unable to not see.

On the right of the painting, we find two prisoners looking at what is happening. Is one of them next? If we return to the main character, John, we find among his pain and torment, a sheep’s wool underneath him, a reference to sacrifice. And if we look closer at his blood, we find Caravaggio doing what artists do: signing his name, but with what? With blood. “F. Michelangelo,” which means “Brother Michelangelo.” This, my friend, is the only time Caravaggio signed a painting. This opens the door to many interpretations, including that Caravaggio is talking about a personal feeling. Caravaggio is a victim of his sins, his foolishness, and his enmities with others.

Final Years: A Descent into Darkness and a Masterpiece of Self-Reckoning

In late 1608, Caravaggio arrives in Sicily. He arrives feeling angry and lonely. The man is fleeing from one place to another, his life in turmoil. And at the time when we think he will learn his lesson and calm down, his fights actually increase! To the point that if someone criticized something in his painting, he would cut it up. He starts to become addicted to alcohol and isolates himself from people. But amidst this psychological collapse, Caravaggio begins to return to his old habit: painting great works of art, like “The Raising of Lazarus” and “The Burial of Saint Lucy.”

In 1609, after getting tired of Sicily, he returns to Naples again. But again, the danger he causes, and which consequently comes back to him, will lead him to be the target of an assassination attempt. An attempt that will leave his face disfigured, to the point that people will think he is dead. You might think his career is over, but no, he will continue to create great paintings again, paintings that embody his internal conflicts.

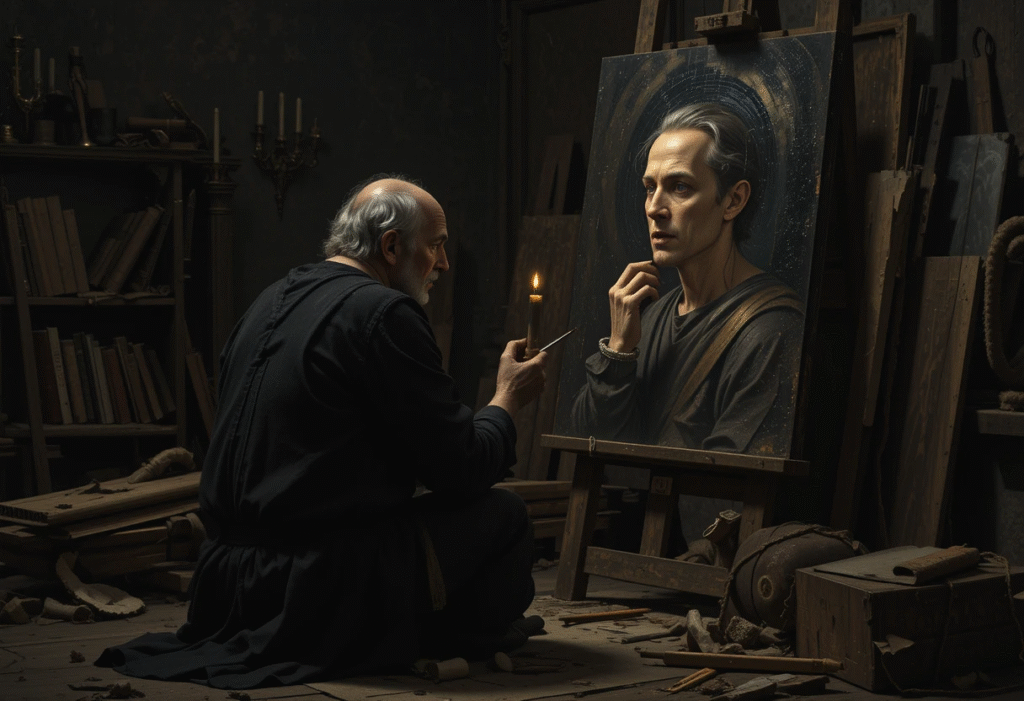

“Every time you slap me, you will get art out of me!” Let’s stop at the painting “David with the Head of Goliath,” which is perhaps his most personal painting and the one that best reflects his psychological state in his final years. The painting depicts David after he has cut off Goliath’s head and defeated him.

David is a young man with a sad expression, holding Goliath’s huge head in his hand. The head of Goliath, whose eyes are open in pain and shock. The unique thing about this painting is that Goliath’s face is actually Caravaggio’s face. And the beautiful reveal is that David’s face is also Caravaggio’s face, but when he was younger.

This is not a painting depicting a religious historical story, but a kind of personal reckoning. The young Caravaggio is holding the older Caravaggio accountable and taking revenge! He is regretful of his decisions, has a desperate desire for repentance, and is trying to overcome the bad side of his personality.

In 1610, news began to come from his patrons in Rome that there was hope for the Pope to grant him a pardon. Here, Caravaggio is convinced that he must return to Rome. And indeed, he sets off on a sea journey from Naples. Unfortunately, he never reaches Rome. On July 28, 1610, a newspaper publishes the news of Caravaggio’s death. And the truth is, Caravaggio’s death will be as controversial as his life. First, it’s uncertain when it happened.

Some historians debate whether he died of a fever while returning to Rome, or from lead poisoning, which was present in high concentrations in the paints he used. Was he killed by his enemies, like the Knights of Malta? In 2010, a study suggested that malaria might have been the main cause of his death. The sad thing is, with this long journey I’ve told you about and these highly important works of art found in the world’s most important museums, Caravaggio died at the age of only 38.

Despite Caravaggio’s relatively short and very turbulent journey, he left us an art that is immortal. He left behind screaming messages of pain, regret, and the search for salvation. And perhaps he was able to leave us this wonderful legacy because of the turmoil that existed in his journey and personality. And if we differ on his paint

Leave a Reply