My dear reader, in 1994, the film The Shawshank Redemption was released. The film revolves around a man named Andy who was unjustly imprisoned. He plans to dig a tunnel in his cell over 19 years, in one of the longest escape plans ever. In reality, my friend, I’m not here to talk about Andy, nor about Morgan Freeman’s role in the film. Instead, I want to talk to you about Brooks.

Brooks was a prisoner living with Andy in the prison. When Andy arrived, Brooks was already there. Brooks, my friend, didn’t escape. He was paroled after 50 years in prison. And now, finally, he was going to be released into the world without any restrictions. He would see life outside the prison where he had lived and been deprived of everything. He would leave the place where he was confined for more than half a century. Finally, he would live like any normal, free human being. He would live as he wanted.

The surprise, my friend, is what we discover when one of the inmates goes to congratulate him on his parole. “Congratulations, Brooks! Welcome back! The iron bars have lost a good man.” Brooks, my friend, would then hold a knife to his throat and threaten to kill him. “Good heavens, Abu Hameed! What is this crazy man doing?! Does he want to go back to prison?! Brooks literally got the golden ticket, he got parole, and now he wants to frame himself for another crime? Why?”

The truth is, my friend, Brooks did indeed want to get a new charge to go back behind prison walls. Brooks reluctantly lets the man go, saying a very strange sentence… “I have no other choice.”

The Burden of Freedom: Brooks’s Terrifying New World

The incident passes, and Brooks, now outside the prison, sends a letter to his inmate friends. He tells them about a terrifying world, more terrifying than prison. The world outside moves at a frighteningly fast pace. He felt that everything around him was a source of danger. Can you imagine, my friend, not having seen the street, cars, sidewalks, laws, or passersby for 50 years? Brooks had forgotten what life was like outside.

Despite Brooks’s words, when we look at the screen and see his situation, we find him describing our ordinary world. Brooks is sitting on a perfectly normal bus, yet he is terrified, looking around, gripping the seat with both hands, even though there is no danger in front of us. The passengers look ordinary and peaceful. Even the job he was supposed to do after his release, he described as very difficult. He writes in the letter that he is struggling to do it.

When we hear this and see on the screen what he is doing, we find that the job is very simple: he is bagging groceries for customers. “Abu Hameed, tell us a real story! I feel like Brooks is being dramatic! He’s dying to go back to the prison mess and eat lentils?! Does he miss the yard time, dancing for the men in the cellblock?! Let him be happy! Freedom is a gift from God.” You, my friend, have put your finger on the secret: freedom.

The film describes Brooks’s suffering in the outside world with a single word: Institutionalized. This, my friend, is a term that describes a person who has lived in prison for a long time. He is a person who had a schedule for everything in his life. The space in which he could move with his free will was very small and limited. In short, he no longer needed to choose anything for himself. Suddenly, my friend, the freedom and choices that we see as beautiful become a burden to him. He is released into a vast, immense, large, huge world.

The simplest thing around him is a threat. The most polite request is a drain on his energy. The kindest people pressure him. Because the simplest act, like riding a bus or bagging groceries, requires a new choice at every moment that he is not used to. Even if that choice is whether to put the tea in first or the milk. Brooks faces the news of his parole with a single sentence… “I’m not going to make it.”

The irony, my friend, is that this sentence describes the opposite of his real fears. Brooks was afraid to go out into a world full of choices that he had to make himself, after being programmed for years to have someone else choose for him.

Choices were imposed on him to the extent that they chose what he would eat and when he would go to the bathroom. And now, he is seemingly subjected to the harshest punishment: after all that, here you go, more choices, more freedom. Suffer! Brooks would say: “I’m tired. I’m tired of being afraid all the time!” Brooks decides to end his sentence with his own hands. Brooks hangs himself in his room. All that’s left is a single sentence he carved on the wall… “Brooks was here.”

Existentialism: The Philosophical Investigation Begins

Imagine, my friend, Brooks hanging in his room, and an investigator comes in to close the case. He will easily rule it a suicide. But a question will remain that is not so easy to answer, a question about the reason for the suicide.

And this will require investigators of a special kind. They will lean over Brooks’s body and write a single diagnosis: Existential Dread. By definition, this is a state in which a person is unable to think and act normally in the world. And with it comes a severe terror that his very existence is a painful and troubling problem, a problem that needs a solution. To the point that when Brooks himself could not bear the anxiety of his existence, the pain of death was much easier for him.

The investigators I’m telling you about could be called existentialist philosophers, after the philosophy of existentialism. These are a group of people who say they have a way to help man interpret his place in existence, or you could say, a way to deal with this existential anxiety. The anxiety we feel with the big questions, like, what is the meaning of life? Or why are we here? The anxiety that can lead to a crisis that destroys a person’s existence, as happened to Brooks.

Of course, my friend, Brooks’s story is fictional, created by the writer Stephen King. And certainly not every person with existential anxiety commits suicide. But the questions that Brooks’s story raises are the questions we want to think about today and see how the existentialists answered them.

Finding Meaning: The Crisis of Identity and Work

The first question people face in life is: “Who am I?” Usually, when you ask people, the first thing they identify themselves with is their job. Because work, you could say, is the constant thing in life. And because of the era we live in, work is what gives their lives value and meaning to their existence.

But the real catastrophe is if this definition is disrupted. Imagine you are a French teacher, and the meaning of your life is in introducing students to a new language. But what if you wake up one morning to a decision that French is no longer a core subject? At that moment, you have a crisis.

The mission that you decided would give meaning to your existence is no longer there. Even if you’re a physics teacher, you will face this crisis at retirement age, when the ready-made definition of “your life = your job” ends. For the first time, you are free from the job. At that moment, you might not see this retirement freedom as a final rest or freedom. At that moment, you will be like Brooks. The retirement you dream of will not be freedom for you it will make you feel lost.

At that moment, you might realize for the first time in your life that your existence depended on something, and that thing, unfortunately, can very well cease to exist. You begin to doubt the definitions that give meaning to your existence, like work. You discover that you were clinging to it because you were afraid of this moment. The job was protecting you from the moment of your anxiety. It’s as if you were a small child hiding behind your mother, afraid of a monster in front of you. But the truth is there is no monster. The real monster is one question: What are you doing? Why are you here?

Brooks, in prison, was the prison librarian. He was an experienced man. All the inmates knew his importance. They would go to him to ask questions and seek his help. He had importance among the inmates. But outside, he was one among millions in a vast world. Or as Morgan Freeman puts it in the film… “In Shawshank, he’s an important man.

Outside, he’s nothing!” Just someone named Brooks. And I want you to notice something very important in the story I told you. When Brooks wrote to the inmates who knew him, he wrote a very long letter. But when he left a message for the people he didn’t know, for the outside world, who would find his body, he wrote only one line… “Brooks was here.” A sentence with which he was trying to assert his being and existence on the wooden beam, after failing to realize it in the real world. This is simply because he suddenly became a person without an identity, without an essence.

Existence Precedes Essence: The Core of Sartrean Existentialism

If you look at the pen in your hand and ask it, “What is the purpose of your existence, pen?” its purpose is to be used for writing. This essence, this being, precedes its creation and existence. The person who made it had already decided before making it that this would be a pen for writing. But the question here is, does this also apply to humans? For most of the history of philosophy and religion, man has been treated with the same idea: his essence preceded his existence. It was determined before he came into the world why he was coming and what his mission was. This is called essentialism in philosophy.

It sees that essence precedes existence. You come with your “catalog” from the factory, and your mission is built-in.

Here, existentialism makes its grand entrance, saying: “Hello, I exist, before my essence.” Existentialism flips this definition on its head. In 1945, the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre would say a very important sentence in philosophy in one of his lectures… “Existence precedes essence.” This sentence would represent one of the most important founding pillars of his existential philosophy.

Sartre saw that you come into the world without a purpose and without an essence. You come into a world that also has no meaning in itself. But your interactions with this world and your choices within it are what determine your essence and the meaning of your life. They determine the meaning of the world around you. This is the most important thing for Sartre: you must choose a meaning for your life.

Here, Sartre would tell you that if you accept the definitions and meanings that society “passes” to you, like your job in this company or your role in this family, then you are deceiving yourself! This is what Sartre calls Bad Faith. They are false definitions that you did not choose. You found them, or someone else chose them for you.

These are like the prison in Brooks’s case. Things we didn’t choose for ourselves, but they became part of our lives, controlling our definitions of ourselves. And according to Sartre, the truth only appears when this candle is extinguished, and everything around you goes dark. Darkness, for Sartre, is the default state of the universe. Because, take this surprise to the face, the truth of the world for Sartre and most existentialist philosophers is that the world in itself has no meaning.

Here we can talk about another important feature of Sartre’s existentialism, which is freedom. If the prison was Brooks’s candle, keeping him occupied and giving him ready-made definitions of himself, then freedom, when it comes, will be unbearable. Because it forces us to face the fact that we are, according to the existentialists, in a world without purpose or meaning.

The freedom Sartre meant here is not chaos, not doing whatever you want, but choosing a meaning for your life yourself, a meaning in a meaningless world, and bearing the responsibility of implementing it, and also bearing the consequences that come from it. Freedom here, my friend, is not a gift; no, it is a responsibility. A responsibility that someone like Brooks collapsed under.

The Myth of Sisyphus: Embracing the Absurd with Albert Camus

Imagine, my friend, opening a book and finding the first sentence says… “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide.” The book I’m telling you about was published in 1942, written by our second investigator in today’s case. Welcome, my friend, the strange man, Albert Camus, and welcome his book “The Myth of Sisyphus.” Sisyphus, in the famous Greek myth, tried to deceive death to live forever.

The gods said, “Alright, just like that? Take eternal life.” The irony is that this was a punishment from the gods. They would make this life a bit tiring. The man would live forever pushing a large rock to the top of a mountain, and upon reaching the summit, the rock would roll back down to the ground, so Sisyphus would have to go down to get it and push it up again, and it falls again, and he goes down to get it, and pushes it up again, and it falls again. He does this forever!

If you reflect, you will find that the horror of the punishment is not the weight of the rock, but the absurdity of it all.

This is what Albert Camus would call “the absurd,” and he would consider Sisyphus a brilliant example of the crisis of our lives as humans. Because, guess what? Our lives, in Camus’s view, are no less absurd than Sisyphus’s punishment! The student who memorizes a curriculum he doesn’t understand to get into a college he doesn’t want, to work a job where he doesn’t like a single person, in a daily 9-hour shift, not counting the commute! All this creates in us the same feeling as Sisyphus. And seeing life this way is what made Albert Camus consider a question like suicide the most worthy of philosophical discussion.

Camus asks… Is death the most rational solution to facing the lack of meaning? Here, if you imagine Albert Camus in Brooks’s room, looking at the body, he would say: “Look, listen to me, the solution is not in suicide, like Brooks before you. The solution is that we adapt to the fact that there is no meaning, and we will even enjoy it.” Suicide, for him, is a cowardly solution.

According to Albert Camus, living with the world and continuing in it, despite recognizing its absurdity, is the solution he sees for man.

Why? Because this is the only brave act that can resist this amount of absurdity. For Camus, the real suffering is not in carrying the rock, but in carrying it without knowing why you are carrying it! And the real freedom is to say: “I am the one who will choose to carry it.” And what? “I will carry it my way, and in my mood. And maybe I’ll carry it while listening to music.” And for these reasons, Albert Camus says at the end of the book… “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Imagine that he is the one who chose the rock, not that it was imposed on him.

The Leap of Faith: Søren Kierkegaard’s Religious Existentialism

Sartre and Camus, my friend, both saw that life in itself, in its truth, has no meaning. But we have one who sees that we create meaning ourselves, and the other who sees that we live bravely and enjoy it. But the existential philosophy also had people who saw that existential ideas could very well coexist with the existence of God. Not only that, but with absolute faith in Him.

Here we find a handsome young Dane named Søren Kierkegaard. Kierkegaard, if he were looking at Brooks’s body, would say that the reason for his suicide was that he did not see the hope that was right in front of his eyes. This man had hope to live, a hope that required nothing from him but a leap. “A leap?!”

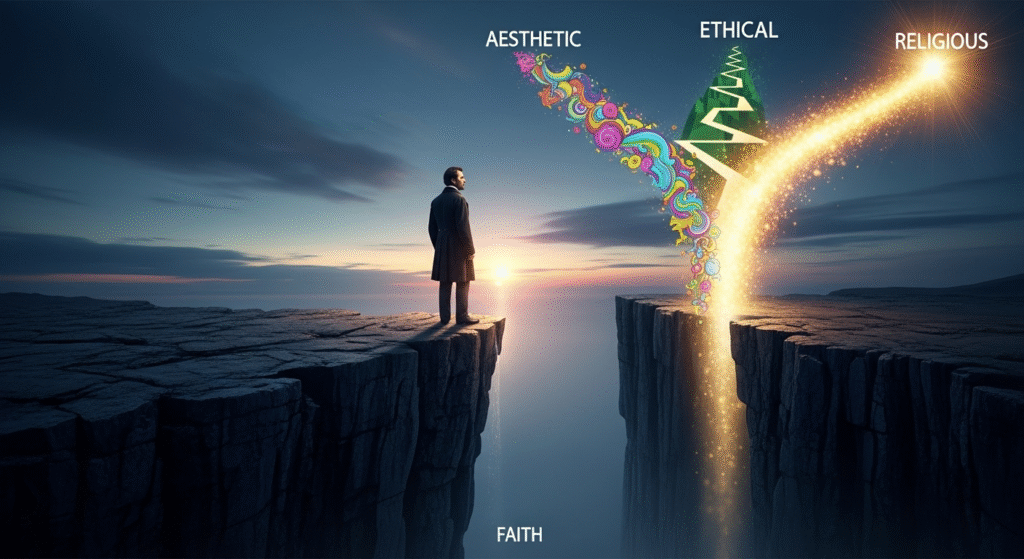

Kierkegaard saw humans as having three spheres in which they ascend: the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. The aesthetic sphere is the first station, where man begins his existential journey. Kierkegaard saw that most people spend their entire lives here. Why? Because man lives his life here for pleasure alone. In the aesthetic sphere, you are likely to get stuck, running from one pleasure to another. After getting worn out in the aesthetic sphere, man says: “No, I want to look for a more responsible life. I want to settle down, I want meaning.” Man tries to live by values like truthfulness, sincerity, and faith. This is the ethical sphere.

But Kierkegaard says: “If you’re happy, remember that this sphere is not enough.” Because ethics here, Kierkegaard means societal laws and norms. Society tells you this is good, and this is bad. “Don’t think for yourself, I will give you the definition of good and bad.” Kierkegaard knew that we needed a new sphere, a sphere where we make our own choices, not by our aesthetic instincts, nor by the recommendations of society. And here, my friend, comes the leap to the last sphere, the religious sphere. Kierkegaard says there is no conclusive evidence for the validity of your faith. Kierkegaard simply sees that if there were evidence, how would it be faith?

It’s as if Kierkegaard, unlike Camus and Sartre, asks, what if, of my own will, in the face of all this absurdity and meaninglessness, I choose faith? Here, Kierkegaard chooses the story of Abraham, the father who is compelled to sacrifice his son, whom he had longed for, without any clear reason other than God commanded him to.

According to Kierkegaard, Abraham was on the verge of sacrificing his son because he made what Kierkegaard calls a “leap of faith.” This is the moment when a person literally jumps out of the spheres of the logical, the obvious, and the conventional. For Kierkegaard, the only thing that makes this life worth living is not because it is understandable, but because you chose to love it and believe in it. You chose to live it, despite everything.

Conclusion: A Philosophy for a Life of Choice

What is common in existential ideas is that existence in life is difficult in itself. This is what Sartre, Camus, Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard agreed on, despite all their differences. They all acknowledge the problem of Brooks, with which we began the episode. They all see that at a certain moment, a person is likely to discover that his idea of the world and of himself may not be real. And when this happens, the person suffers a terrifying crisis of meaning.

Perhaps the best description of the human creature is the words of the existentialist Gabriel Marcel, who says that we are creatures who have received existence because it is a gift, and our role is creative fidelity to this gift. A fidelity based on us thinking and choosing, thinking and choosing how we will use this existence of ours. This is the most important thing that existentialism teaches, whatever its different answers. A question of just three words, my friend, “Why am I here?”

Leave a Reply