Let’s go back to 2006, to August 31st. Trust me, the event is worth it. It’s the US Open, and we’re witnessing the final match of the American legend, Andre Agassi. The player, 36 years old at the time, stood to greet the crowd, ready to play. But beneath the pristine white tennis clothes, a very dark battle was raging within his body. Agassi entered the tournament suffering from a chronic back injury and was taking painkilling injections before almost every match.

In the second round, he faced the Cypriot star Marcos Baghdatis. This match, my friend, was an epic. It lasted for four hours, finishing well after midnight. For the first two hours, it was an exciting and well-played match. After 11:30 PM, it was no longer a laughing matter. The players went on for too long; four hours is a lot. When the match finally ended, as is customary in tennis, the two met at the net and shook hands elegantly. But as soon as both players left the court, they were on stretchers in the physiotherapy rooms, screaming in pain.

“Why were they screaming, Abu Hameed? Is a tennis court anything compared to a football pitch? It’s just a few meters by a few meters they’re running across from each other. They don’t even touch.” My friend, let me tell you that in a match like this, a tennis player can run an average of 12 kilometers. This is besides the mental focus, tracking the ball with their eyes, game strategy, and facing the opponent. Not to mention the powerful, precise shots required.

A Champion’s Secret: “I Hate Tennis with All My Heart!”

Let’s get back to our match. It ended with Agassi’s victory, and as I told you, with great difficulty over four hours. This match would be the last in the career of one of the greatest tennis players of all time. Agassi himself would later tell us the details of that day from the beginning. He said: “I woke up at 7 AM, not knowing where or who I was.

This feeling of being lost wasn’t new to me, but this time it was deeper. I looked around and found myself on the floor, not on the bed. The floor had become much more comfortable for my back. After waking up, I count to three, take a deep breath, curl up like a fetus, and wait for the blood to circulate in my body again so I can get up.”

“I was a 36-year-old man, but my health was that of a 90-year-old! After 30 years of mental pressure, jumping, and running, my body was no longer my own, and my mind was not mine. The moment I open my eyes, I feel like a stranger, and I quickly review the basics: my name is so-and-so, my wife’s name is so-and-so, we have a son and a daughter, we are currently in a hotel in New York, and I am about to play the last tournament of my life.” And listen to this part. He would say: “I play tennis, even though I hate it with all my heart! And I’ve hated it for a long time!”

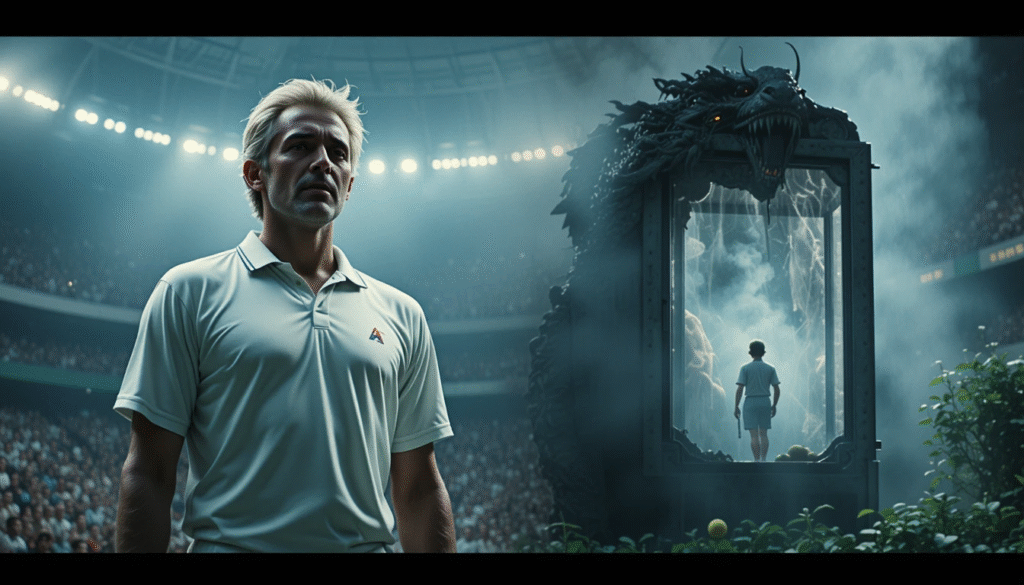

This is the introduction Agassi used to begin his autobiography, Open, which was released in 2009. Agassi says that at the age of seven, he was under the control of a harsh, tennis-obsessed father. A father who saw talent in Agassi and turned his life into a training camp. One time, his father came in with a machine that looked like a dragon.

The boy was happy, thinking it was a toy he could play with and break. It turned out to be a ball-throwing machine, firing balls at an insane speed in all random directions. The father forced his son to hit thousands of balls every day. His father used to tell him, “If you hit 2,500 balls a day, you’ll be hitting almost a million balls a year. And I don’t think anyone who hits a million balls a year can be beaten.”

Andre says: “My father didn’t just want me to hit the balls; he wanted me to defeat the dragon that throws the balls. How could I win against something that never gets tired?! Also, my father raised the net by 15 cm to make it harder for me, telling me: ‘Anyone who can get the ball over this 15 cm higher net can clear the Wimbledon net with their eyes closed.'”

The truth is, my father was right. The one who hits a million balls and clears the extra-high net would surely become a tennis legend. But there’s a small problem, Dad. I don’t want to go to Wimbledon! I don’t want to clear their net! Every day I ask myself: is there another life besides tennis?!

Despite his success and fame, Agassi lived years of loneliness, pressure, and confusion. In the nineties, for example, his ranking dropped to 141st, and he fell into a cycle of drug use to try and find himself. Even at the peak of his fame, he didn’t like his image as a tennis player, nor did he even like tennis attire. Even his famous hairstyle was a wig. In short, Agassi was a miserable person trying to play the hero—not the hero he wanted to be, but the one people wanted to see. A hero for everyone except himself.

Beyond the White Uniforms: The Deceptive Elegance of Tennis

Agassi’s story is shocking, not just because his father turned him into a commercial project, but because it shatters the first impression one might have of tennis: that it’s a lighthearted sport for people dressed in white, playing in gardens under the sun.

It seems more like a commercial for laundry detergent than a competition! Agassi reveals in his book how the pressure to achieve in tennis can be devastating, and how every match is a psychological battle before it’s a physical one. In tennis, you’re not a team. There are no ten others to push you. If you’re tired, you can’t be substituted. You play alone on the court for hours. You think alone, you run alone, you play in a very limited space, and you’re not allowed to talk to or blame anyone but yourself.

Here, you must ask: is tennis really a sport so harsh that it could make one of its champions hate it? And is it really a means of social climbing to the point of obsession, like Agassi’s father had? These are questions that are difficult to answer without delving into the history of the sport—a history with historical and social roots much deeper than you can imagine.

From French Monks to Royal Courts: The Early History of Tennis

If you’re an art lover, I want you to look at a beautiful painting with me: The Death of Hyacinth, painted by the Italian artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. The painting’s theme is taken from the book Metamorphoses, which tells the tragic end of the young Hyacinth.

According to the legend, while throwing a discus in a sports competition, it hit him in the head, and he died. The god Apollo tried to save him but failed, so what did he do? He turned him into a flower. Tiepolo painted the flower beautifully in a corner of the painting, but he played with the story a bit and replaced the discus with a tennis ball and racket, suggesting that the ball is what killed Hyacinth.

Or let’s turn to literature. In Shakespeare’s Henry V, a basket of tennis balls is presented to the king as a form of mockery, implying he is just a little child unfit to rule. Both the painting and the play are compelling evidence that the game began centuries ago. Some trace its origins to Italy, where it was called “pallacorda,” because the ball had to pass over a rope, not a net. Other historians say tennis began in the 12th century in the monasteries of northern France. At that time, there were no rackets; the monks played with the palm of their hands. From here came the French name for tennis, “Jeu de Paume,” or “game of the palm.”

Over time, it is said that people started using gloves, and then the first wooden rackets appeared in the 16th century. The word “tennis” likely entered English in the 14th century, originating from the French word “Tenez,” which means “take” or “receive.” This was the phrase the server would say.

The game became incredibly popular among the nobility of France and England because it required a large budget for huge, enclosed courts. King Henry VIII, for instance, was so addicted to the game that he built private courts inside one of his palaces, Hampton Court. Over time, tennis became a sport associated with the upper class, giving them a space to interact, form alliances, partnerships, and marital ties, all away from the public eye.

The Birth of Lawn Tennis: How a Lawn Mower Changed Everything

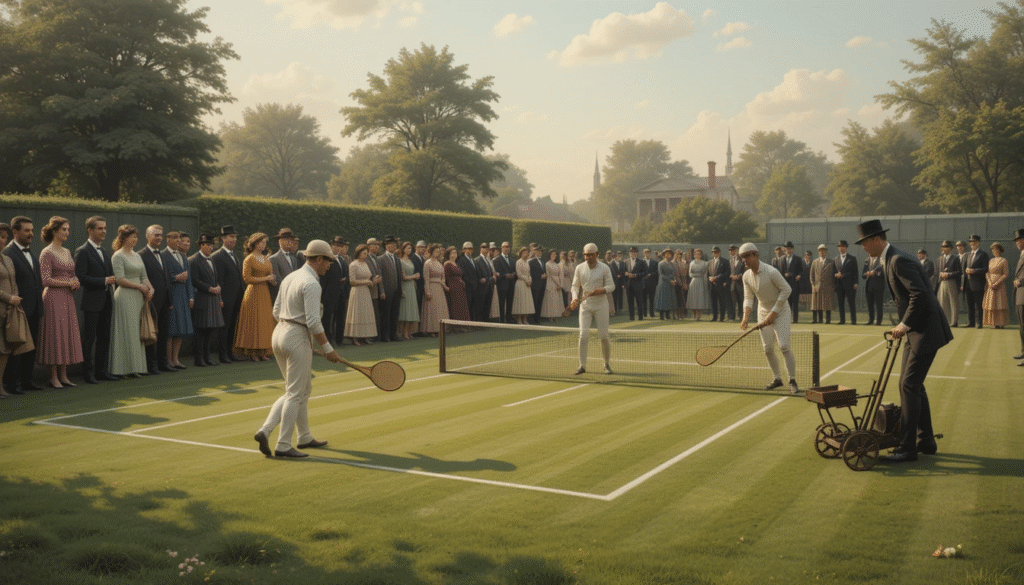

So what caused this elite sport to spread like wildfire? In his book, A People’s History of Tennis, author David Berry attributes the spread and evolution of tennis to two main reasons. The first, my friend, was the invention of the lawn mower in 1827. When we could mow the lawn anytime, it became easy to have a garden anywhere. The second reason was the invention of vulcanized rubber in 1844, which made the balls bouncy and suitable for playing in gardens.

David documented the first modern tennis match on May 6, 1874. It was the first match played on grass, in London. The idea came from Walter Wingfield, an aristocratic English officer with a business mind. He decided to invent a game he called “Lawn Tennis.” Wingfield set up an hourglass-shaped court, brought a somewhat high net, wooden rackets, and rubber balls, and invited three friends to play a doubles match with him. As they played, people gathered to watch. The game looked simple from a distance. All you had to do was hit the ball with the racket over the net and into the court.

But as anyone who has played tennis knows, it’s not easy at all. It turned out to be very difficult. The balls would hit the net or fly completely out of bounds, amidst the laughter and ridicule of the club members and the press, who were sure the game wouldn’t last.

But surprisingly, tennis did last and spread like wildfire! Within a year, tennis was everywhere in Britain, and soon it became a trend worldwide. The reason was simple: despite its difficulty, the game was fun, and its equipment was available. But there’s another, more complex answer: society was ready for tennis.

We are in the late 19th century, Britain’s landscape is changing, industry is growing, and the middle class is expanding. According to sociologist Robert Elias, tennis courts were where the ambitions of the middle class met the anxieties of the upper class. The game allowed professionals to meet nobles on the same court and play together in a refined, sporting atmosphere. Tennis was also marketed with a luxurious style. Wingfield was a shrewd marketer, packaging the entire kit—net, rackets, and balls—in a chic box and advertising it as the “game of nobles,” open to both men and women.

Wimbledon and the Rules That Shaped a Sport

In 1877, the All England Club in the Wimbledon suburb of London decided to organize a national lawn tennis championship. Henry Jones, the idea’s originator and the tournament’s referee, sat down with the organizers to set the game’s rules. They replaced the hourglass court with a rectangular one, lowered the net height, and changed the scoring system to the French “Jeu de Paume” system. That’s why viewers often get confused by the score! A game is four points, but they are not counted 1, 2, 3, 4. No, they are counted 15, 30, 40, and game point. A player must also win six games to win a set, and two or three sets to win the match.

No one has a clear answer as to why the numbering system is this way, but the closest theory suggests it comes from a clock face, with each point representing a quarter of an hour: 15, 30, and instead of 45, they said 40 to avoid confusion. The tournament organizers also set a dress code: all white. This was to reflect the elegance the tournament represented. Over the years, fashion brands began to capitalize on this dress code. And you can’t talk about Wimbledon without mentioning strawberries and cream, an iconic tradition since 1877. The first Wimbledon championship was a smashing success and remains one of the most important tennis tournaments in the world today.

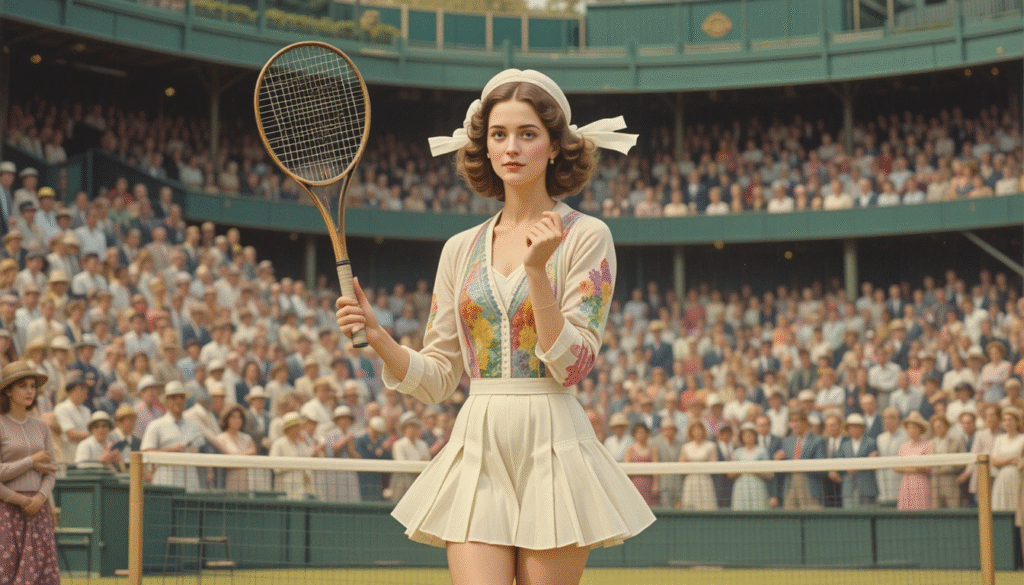

Suzanne Lenglen and the Dawn of the Open Era

The real turning point for tennis’s popularity came after World War I. At Wimbledon in 1919, a French girl named Suzanne Lenglen made history not just with her distinctive play, but with her style and presence. She wore a shorter skirt for her time, a colored cardigan, and a silk ribbon on her head like a ballerina. Between points, she would apply makeup and greet the crowd. From 1919 to 1926, Suzanne lost only one match, winning 21 titles and two gold medals.

In 1926, Suzanne broke the biggest taboo in tennis: she decided to become a professional player, playing for money. The culture at the time was that tennis was for amateurs, not professionals. A professional was seen as a mere mercenary. Suzanne’s decision was shocking, but it set the precedent for stars who came after her. She signed a $75,000 contract for an exhibition tour in America, and every move she made was sponsored. Suzanne changed the face of tennis and further boosted its popularity. By the time of her death in 1938, the number of participating countries in major tournaments had grown from 7 to 38.

The next event that took tennis’s popularity to another level was in June 1937, when the BBC broadcast the first live tennis match from Wimbledon. Television began to draw a new audience to tennis who knew nothing about the game. By 1961, viewership was exploding, with 14 million people watching the women’s final. In 1968, the “Open Era” of tennis began. The time of amateurism was over; tennis became a sport of fame and fortune.

The Big Three: A Golden Age of Rivalry

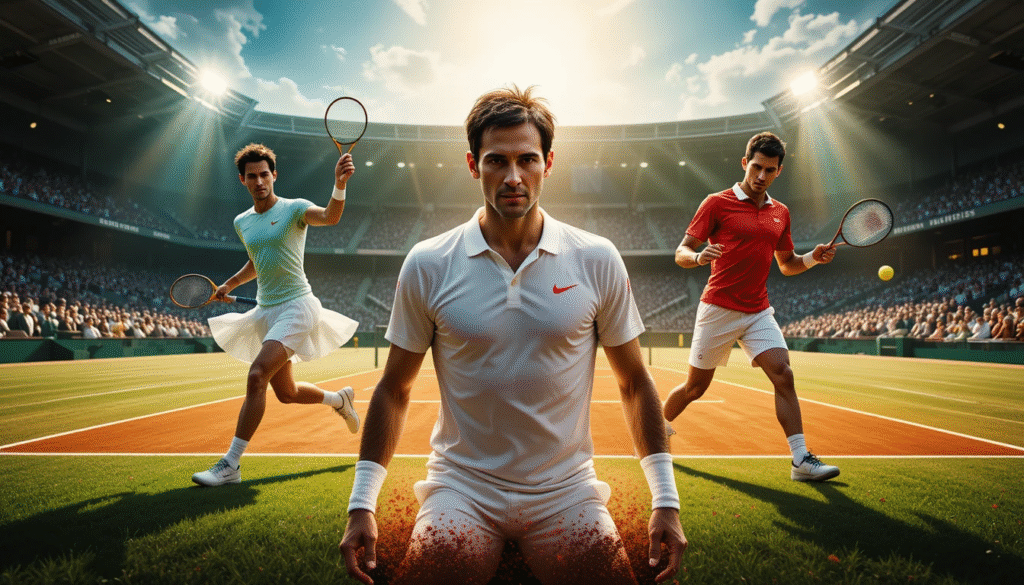

Men’s tennis in the modern era would be defined by the “Big Three.” In 2003, the Swiss prodigy Roger Federer emerged, a maestro who would capture the hearts of millions. Federer didn’t just play tennis; he danced ballet. His movement on the court was so graceful and calm that people thought he won effortlessly, which greatly annoyed him. “Ease is a myth,” he once said in a commencement speech. Federer ended his career in 2022 with 20 Grand Slam titles.

But no great story is complete without a formidable rival. Enter Rafael Nadal, the “King of Clay,” a phenomenal Spanish teenager who stormed onto the scene in 2005. “Rafa,” as he’s known, was a bull on the court, fighting for every point as if it were his last. His uncle and coach, Toni Nadal, had him play left-handed from a young age, even though he was right-handed, creating a nightmare for his opponents. His signature forehand had a vicious topspin, rotating at 3300 RPM. Nadal ended his career in 2024 with 22 Grand Slam titles, including an astonishing 14 at Roland-Garros.

Despite the dominance of Federer and Nadal, there was always a third player in the mix, a Serbian player constantly trying to surpass them. After years of effort, he changed his entire diet—no crepes, no pizza. That player is Novak Djokovic. Nicknamed “The Joker,” Djokovic worked on his body’s flexibility and his mental endurance. He studied every opponent, anticipated every shot, and won even under the worst conditions. While the crowd was often against him, Djokovic kept collecting titles. The tortoise kept crawling until he was at the top of the numbers, with 24 Grand Slam titles—more than Nadal, Federer, and even Serena Williams.

The Mental Battlefield: Unpacking the Psychology of Tennis

Now that you know everything about the game, its history, and its legends, let’s try to understand the game itself. What makes a simple game exhaust a champion like Agassi, make Djokovic smash his racket in anger, and lead Federer to give a whole lecture on how it’s not easy at all?

First, there’s the serve. The average serve speed reaches 180 km/h for women and 200 km/h for men. The ball moves so fast that conscious perception can’t keep up, meaning tennis players return serves subconsciously. In the book The Inner Game of Tennis, the author argues that the biggest problems for tennis players are not in the fundamentals of movement or physical condition, but are related to the player’s mental state. If you enter a match thinking your stronger opponent will win, you’ve already lost.

The book talks about two selves. “Self 1” is the conscious mind, the one that speaks in your head, judges you, and compares you to others. The problem with Self 1 is that the more you think and analyze, the further you get from the spontaneous feeling of body and movement. “Self 2” is the body and the unconscious mind, the automatic part of you that moves naturally without instructions. The power of Self 2 is that it is the one that actually plays. A match is a split-second decision; there is no time for thinking.

To strengthen Self 2, you need to train more and more until the movement, the shot, its direction, and its power are “saved” in your hand. You don’t think about it to do it. That’s why Agassi’s father made him hit 2,500 balls a day—so he wouldn’t think while hitting. The secret for a great player is to create a space of trust between Self 1 and Self 2. This is why top players often start grueling training at age 4 or 5, with zero social life, zero friends, zero family. That’s why Agassi says, “Tennis is the loneliest sport.”

Perhaps the best sentence to end this episode with is from the player Billie Jean King. I think now, my friend, you can see tennis with different eyes. Beyond its elegance and calmness, you can see its difficulty, its violence, and its cruelty to its champions. And paradoxically, this perspective might make it an even more enchanting game in your eyes.

Leave a Reply