In the year 1871, we see Ahmed Abdel Rassul herding his goats in the village of Qurna, west of Luxor. We watch as a goat strays from the herd and disappears into the mountain. Ahmed Abdel Rassul runs after it until he reaches a strangely shaped well. The goat had led him to a place he would return to that night with his brother, Mohamed. Ahmed would light the lamp, and his brother would descend with a rope. Mohamed would discover that the well was very deep, reaching 10 meters. Eventually, he would reach the bottom and, indeed, find the goat waiting for them.

You might think that Mohamed should be overjoyed to have found the goat, but Mohamed wouldn’t focus on the goat at all, as if he hadn’t come down for it. His eyes would be fixed on the entrance of a Pharaonic tomb where the goat was standing. He entered to find coffins and treasures estimated to be worth millions. Here we arrive at one of the greatest archaeological discoveries of the 19th century: the Deir el-Bahari cache. We reached it, my friend, by way of a goat. This true story would become the basis for Shadi Abdel Salam’s The Mummy.

A Stray Goat and a Royal Secret

To understand how the Deir el-Bahari cache came to be in this place, we must go back to the rule of the 21st Dynasty. At that time, the priests were fearful because the royal tombs were being robbed. They decided to move the royal coffins in a massive project supervised by a priest of Amun named Pinedjem II. A tomb was established in the heart of the mountain at Deir el-Bahari—a tomb, my friend, containing 55 mummies of Egypt’s greatest kings: Ramesses II, Thutmose III, and Ahmose I. They had created the ultimate dream for an antiquities dealer! Instead of going from tomb to tomb, the dealer could find them all in one “lot.”

Returning to our brothers, Mohamed and Ahmed. The two would sell pieces and papyri from their findings to a man named Mustafa Agha Ayat, who was an agent for consulates like Belgium and Russia. Why am I telling you this? Because someone working in a consulate has diplomatic immunity. It helps him pass through checkpoints. Consequently, he turned it into a business, leaving Egypt full and returning from Europe empty. This led to Europeans being surprised by the appearance of artifacts from the 20th and 21st Dynasties of unknown origin. Gaston Maspero, the director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service at the time, alerted the authorities. Gradually, the investigation led to the Abdel Rassul family.

Ahmed and his brother were summoned before the governor of Qena, Daoud Pasha. He would say, “Your Excellency, I swear I know nothing. I saw no goats, we didn’t go down a well, none of that.” They even brought witnesses to testify to their good character, so they got away with it. What happens next, my friend, is that discord begins to creep in between the brothers.

A dispute arose until Mohamed Abdel Rassul decided to reveal the secret. He went to the authorities and said, “I want to be a state witness.” So in 1881, the authorities came and extracted the cache in a procession leaving from Karnak amidst the cries and screams of the locals. It is said that a great storm arose that day, never to be forgotten.

Shadi Abdel Salam: The Historian Behind the Camera

This, my friend, is the end of a story that would remain unknown for many years, famous only among archaeologists. But 88 years later, the story would become incredibly famous, because in 1969, the film “The Mummy” (Al-Mummia: The Night of Counting the Years) was produced—the first feature film by one of the most important filmmakers in the history of Egypt, Shadi Abdel Salam.

Although this was his first film, he was well-known in cinema circles. You probably know him and have seen much of his work, because simply put, Shadi Abdel Salam was one of, if not the greatest, production designers in the history of Egyptian cinema. All the costumes and sets for Wa Islamah, Saladin the Victorious, Amir al-Dahaa, and Bride of the Nile were his designs. Think of how many eras, clothing styles, and architectural designs those four films cover!

It’s easy to see that Shadi Abdel Salam was obsessed with history, and his excellence in his craft came from this. For instance, to design the sets for Wa Islamah, he read the manuscripts of Al-Maqrizi. As a result, the costume of Sultan Aybak in the film matches Al-Maqrizi’s description of Baibars in his manuscripts. His dedication would impress the directors he worked with, to the point that Youssef Chahine would say the costumes in Saladin were more beautiful than his own direction of the film. Shadi Abdel Salam’s school of design made him a globally sought-after name, even leading him to work on the film Cleopatra (the 1963 version, not the Netflix one).

During this time, the Minister of Culture, Tharwat Okasha, asked the Italian director Roberto Rossellini to recommend screenplays that could elevate Egyptian cinema. Rossellini read the script for “The Mummy,” which took Shadi Abdel Salam years to write, pouring his love for Egyptian history into it. Rossellini was extremely enthusiastic and convinced the minister that they had a unique, “authentic Egyptian film.” To make “The Mummy,” Shadi turned down fantastic offers to work on the set designs of many other films.

He then faced a financial crisis, which turned into a psychological one after his father’s death and the 1967 military defeat. Yet, amidst all these crises, Shadi finished his film. Once “The Mummy” was released, the status of Egyptian cinema changed forever. It toured international festivals like Venice and Berlin, won the prestigious Georges Sadoul Prize, and was hailed as a turning point.

Why is “The Mummy” So Hard to Watch, Yet So Important?

I understand, my friend, that the film is not to everyone’s taste. But let me explain how this film achieved its global status, and I believe your perception of it will change completely after what I’m about to say.

Dim the lights, my friend, prepare your popcorn, and let’s watch the film together. Our film begins with a Pharaonic mask, one eye open, the other missing, as if in a state between sleep and wakefulness. The music sounds like the humming of sad souls. In front of us, a text appears, written in the present and future tense, offering a promise: “O you who go, you shall return. O you who sleep, you shall arise. O you who pass on, you shall be resurrected.”

Shadi Abdel Salam decides to start his film from a very different perspective—not that of the thieves, nor the archaeologists, but from the perspective of the stolen goods themselves. He gives you the point of view of the cache itself, showing the perspective of the past kings who died in peace, believing they would be safely resurrected.

But what happened was that their tombs were violated. This leads us to the next scene, where we see archaeologists Maspero and Ahmed Kamal reading lines as if receiving orders from the past kings, a message to save them. This, my friend, is a papyrus from the “Book of the Dead,” which the deceased recites to remember his name. Because in their belief, if a pharaoh was resurrected having forgotten his name, he would wander forever in eternal suffering. The loss of a name equals the loss of identity.

From the beginning, Shadi Abdel Salam defines the core of his film. This isn’t a story about theft or a police chase. It’s about a memory of the past that must be resurrected.

The Horabat Tribe: Guardians and Prisoners of the Past

Shadi also made a bold decision with the dialogue, having all characters speak Classical Arabic. This is because it’s a more universal language, more likely to endure. He believed that while dialects change, Classical Arabic would always be understood, as if telling us that the problem of the cache is a problem for every Egyptian generation, regardless of time or place.

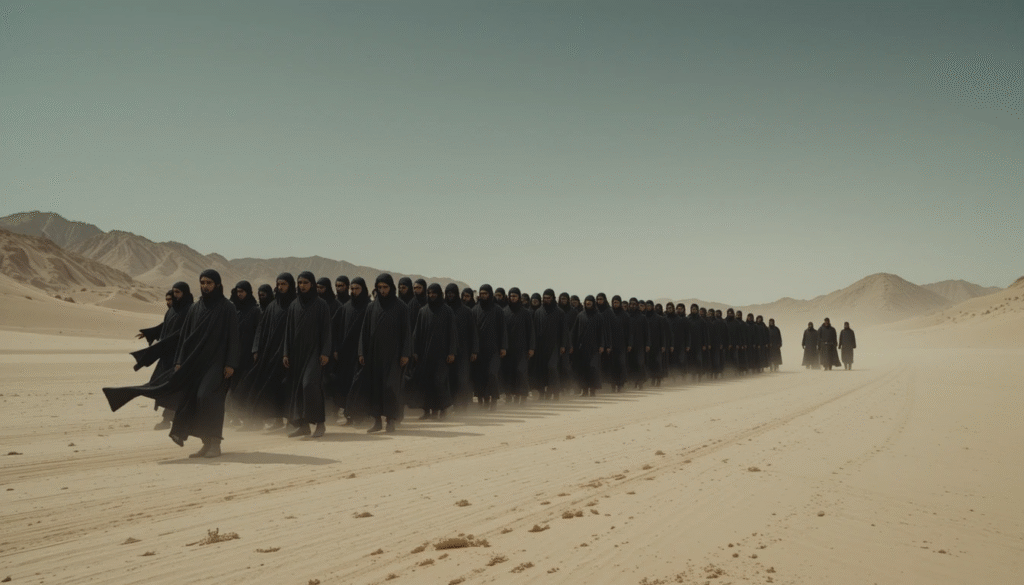

The scene ends with the decision to go to Thebes to search for the cache, leading us to the Horabat tribe, the film’s representation of the Abdel Rassul family. A 500-year-old tribe that has never left the mountain nor mixed with the people of the valley. Shadi Abdel Salam visually emphasizes their isolation: sky, desert, a vast, empty frame. The people stand like stones, their clothes moved by the wind, but they themselves do not move. They are all dressed in black, like ghosts, as if they had died long ago. To be a member of this tribe, you must lose your individuality.

Today is no ordinary day for the tribe; it is the funeral of their leader. As everyone goes about their business, one person decides to look at the camera, at us, as if to say, “I am the hero of this story.” This is Wannis, the leader’s son, the only one whose name we will learn from the Horabat men, because he will be the only one different from them, the only one with his own personality, individuality, and, most importantly, innocence.

Wannis’s Crisis: A Conflict of Conscience

This is no ordinary funeral. It’s a ritual of succession. In the Horabat tribe, the death of the leader is the moment his sons learn the tribe’s secret: the cache. They learn that from this day on, their lives are not their own; they will dedicate their lives as new leaders to plundering these tombs. We see Wannis and his brother standing before their uncle, black shadows just one step away from becoming guardians of the tribe’s secret. A transformation that requires one thing: surrendering their will to their elders.

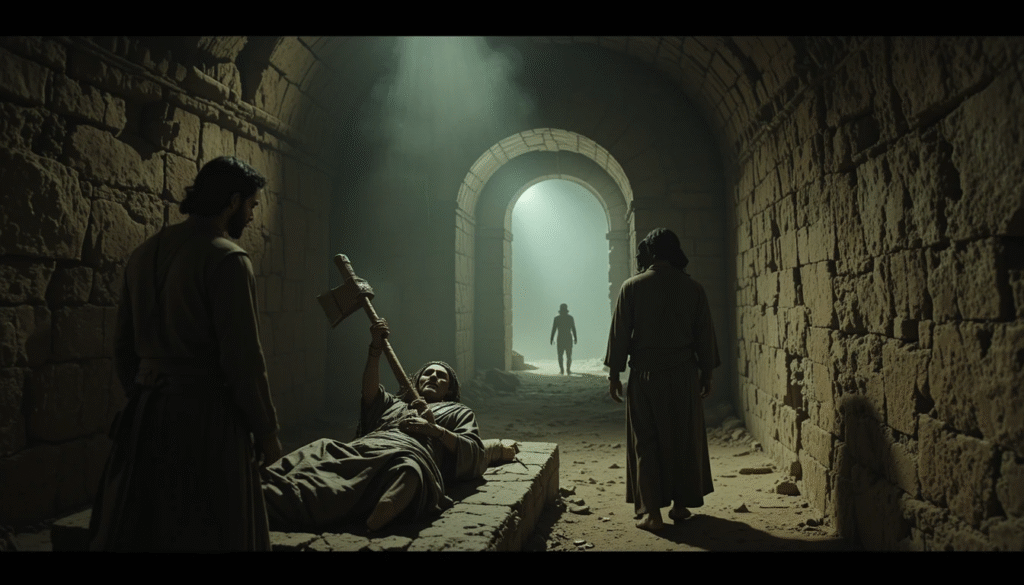

After a majestic funeral honoring the deceased, Wannis and his brother find themselves in a tomb. But here, the deceased is subjected to the most heinous violation. The uncles violently unwrap the linen from a mummy to take the necklace, cutting off the mummy’s neck with an axe to get it. Wannis and his brother are shocked to discover that the tribe’s life above ground is completely different from its life below, and that the tribe’s existence is based on violating the sanctity of the dead. It’s a seismic moment.

“What is this secret? You have made me afraid to look at it!” Wannis cries at his father’s grave. You might expect action and fights, but that’s not what happens in “The Mummy.” The director takes us on a long, quiet shot of Wannis. We see him walking down a narrow corridor, feeling trapped. The critic Mohamed Shafik notes that Shadi plays with time in reverse.

Thrilling events like seeing the mummy or Wannis’s escape, which are “strong times” in cinema, are shown as quick, ordinary scenes. In contrast, he takes his time with “weak times,” moments with no surprises. Wannis moves slowly, touching the walls as if bound, suffocated. Shadi inverts the time equation to say that what is more important than external events is the internal one: the shock within Wannis’s conscience.

The “Pharaonic Rhythm”: A Visual Language of Entrapment

Did the tribe’s leaders feel they were desecrating the dead? The truth is, their logic was simpler. As the uncle says, looking at the Pharaonic eye necklace: for them, the cache was just buried treasure, nothing more. It was a treasure that could sustain a poor village in the mountains. The very idea of stealing antiquities, which we now consider a crime, was not legally clear at the time. We have only understood the value of antiquities for about a hundred years. Before that, they could be sold on sidewalks.

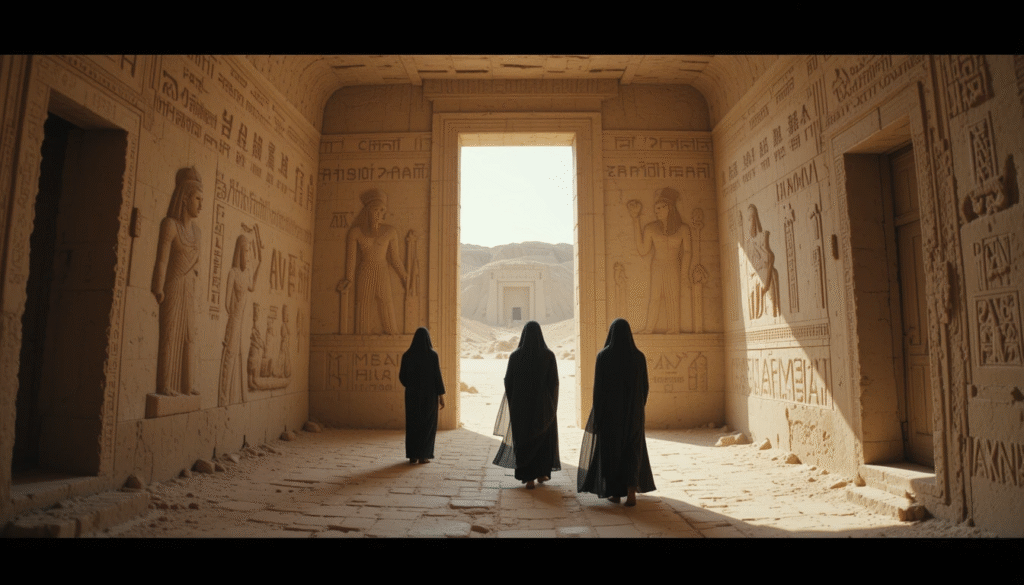

The tribe is surrounded by the artifacts of their ancestors but feels nothing but the importance of their own survival. If you look at the composition of the leader’s widow’s home, you feel like you are looking at a Pharaonic composition on a temple wall, as if seeing Queen Isis mourning her dead husband. Shadi Abdel Salam painted all his film’s scenes as if they were Pharaonic murals. The walls behind the characters are adorned with Pharaonic inscriptions. They live within history but do not consider it their own, which gives them the license to violate it.

Shadi Salam imposed what he called the “Pharaonic rhythm.” The tribe members move very slowly, partly due to the heat of Upper Egypt, but also for an artistic reason: to make them appear like statues or figures in murals. It’s as if the curse of robbing their ancestors’ history has turned them into their ancestors—trapped in the mountain, their movements dead, just as the memory of the dead Pharaohs is trapped on the temple walls.

The Other Robbery: Colonialism and the Erasure of Egyptian History

The older brother decides to escape, telling Wannis, “Our mother lives in the past. Come, escape with me to a future outside the tribe.” But Wannis cannot escape. His problem is bigger than his future; he must first know his past. Not just the past of his tribe, but the past of all his ancestors, down to the mummy he saw. Shadi expresses this with brilliant, wordless scenes of Wannis in the presence of temple statues, appearing as an extension of them.

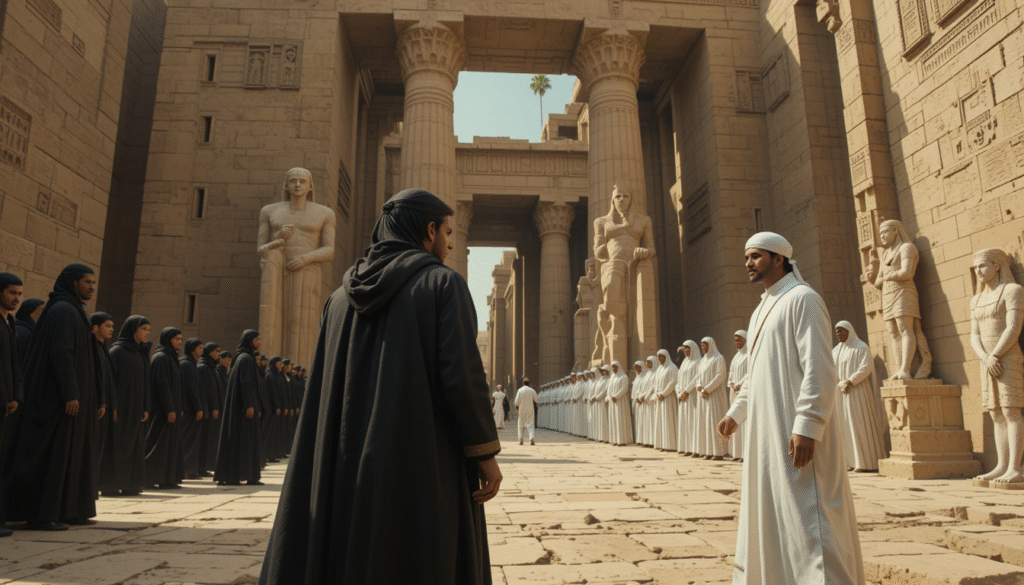

At the moment of the brother’s death, we hear the siren of a steamboat. The outside world is coming. The officials, led by the archaeologist Ahmed Kamal, arrive. At their first meeting, we see Wannis, the son of the tribe, wearing dark clothes, the color of the tribe’s curse and its secret. Everyone who comes from outside the village wears white—the color of light, the color of revealing the secret.

The archaeologist Ahmed Kamal is a stranger to Thebes, but because of his knowledge, he is able to understand everything around him. Compare this to the scene where we see Wannis, a son of Thebes, from a diminutive perspective in front of giant walls, representing his ignorance but also his vast curiosity.

The director presents three characters: Wannis, the “Stranger” from the valley, and Ahmed Kamal, the official from the capital. All three are Egyptians, their history is one, but their position towards that history is completely different. Shadi expresses this through makeup. All the Egyptians in the film have a uniform dark skin tone, a rare makeup called “The Egyptian,” created by Max Factor specifically for Cecil B. DeMille’s film “The Ten Commandments.” Shadi wanted to unify their appearance to tell us that we are all descendants of this civilization.

A Film Bigger Than Life: The Enduring Legacy of “The Mummy”

In the end, Wannis reports the secret of the cache to Ahmed Kamal. The officials begin to bring out the coffins, and with each one, they speak its name. As the name is spoken, we finally hear the prayer of resurrection: “Behold, your bones are gathered, your heart returns to you. Here you are in your beautiful form, living and resurrected.” Shadi presents one of cinema’s greatest finales: a procession of mummies, depicted as a resurrection of the kings of Egyptian civilization. The tribe members, in their black clothes, watch bitterly as their treasure is brought into the light. Wannis turns his back on his tribe, which will never forgive him.

The film, which began with a written promise, ends with a command: “Arise.” As if the story is not just about Wannis, but about every Egyptian watching the film. The message is that the Egyptian’s duty is to rise, to recognize the memory of his past, and to protect it in order to understand his future. This is the very idea Shadi Abdel Salam summarized when he said… “A people without memory is a people without a future.”

Perhaps the real story of “The Mummy” is far more dangerous than the film’s plot. The film’s villains were the tribe’s elders, but Shadi’s goal was not for the audience to hate the tribe. It is a story of a complete history and a memory of the past. If a person does not know how to guard it, he will lose his future. The real villains were the colonial powers.

The European founders of Egyptology, along with weak laws protecting antiquities in Egypt, were the cause of many of our artifacts leaving the country. It is also the reason why Egyptology, to this day, has not been freed from its view of the modern Egyptian as an intruder on his own history, not a part of it.

Shadi’s problem was that the Abdel Rassul family were Egyptians, and their responsibility was greater because it was their heritage. “The Mummy” is a story of the resurrection of history and knowledge that can only be undertaken by the Egyptian.

The Egyptian is solely responsible, and no one else. In 2009, Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation restored the original version of the film. In 2021, AI enhanced its quality to 4K. It’s as if the film, whose concern was memory and resurrection, turned itself into a document—a document that was remembered and is being resurrected anew. A document not just for Egypt, but for the history of cinema worldwide. A document titled “The Mummy.” And that, my friend, is all.

Leave a Reply